Practical Ways to Support Autistic Girls to Thrive in School

Jan 09, 2024

by Dr Becky Morgan, Educational Psychologist

In my doctoral research I explored the way that language and discourse impacts the self-concept and social-identity of autistic adolescent girls. Various personal and professional reasons led me to this area of study, but one major influence was my experience of working with autistic adolescent girls who were struggling to stay in school.

When I looked at the research literature, at news articles, and when I listened in to what autistic girls were sharing (for an example see: High school isn’t for everyone - The Donaldson Trust (donaldsons.org.uk)), I came to see that this was not an isolated phenomena. Autistic teens are really struggling with the mainstream school environment, for various reasons, and this is having a negative and worrying impact on mental health and wellbeing.

In a systematic review into the school experiences of autistic girls and adolescents, Tomlinson et. al. (2020) found:

- Difficulties with sensory overwhelm, managing transitions, the structure of lessons, unclear instructions and expectations about peer collaboration

- Parents reported schools misunderstood their daughters needs in relation to autism, and in most studies parents assessed their daughters needs as greater than school staff did. School staff could be sceptical or entirely dismissive of parents concerns, with teacher knowledge about autism being dominated by more male oriented presentations of autism

- Masking was frequently reported, and it was recognised that this resulted in negative mental health outcomes

- Friendships were a source of significant stress, with girls being more socially motivated than autistic boys, but with frequent experiences of exclusion, bullying and being overlooked, there was a greater risk of being shunned by mainstream peers in adolescence. Girls tended to gravitate towards other girls with autism where this was possible

Based on these findings, and on my own doctoral research with autistic girls, these are some of the practical ways I propose we can better support autistic girls to thrive in their time at school:

1. Support the whole school community to understand & accept neurodiversity:

Whilst there is a real need for schools to increase their understanding of the way that autism often presents in girls (and a clear role for Educational Psychologists to support this), there is a risk that keeping the focus on ‘within-child’ factors and specific accommodations allows business-as-usual to continue. And we know that business-as-usual is not working for a lot of autistic girls in secondary school (see Walk in My Shoes - The Donaldson Trust (donaldsons.org.uk)). Furthermore, other neurodivergent learners are struggling – often with the same things – and if estimates are correct, at least around 1 in 5 learners are thought to be neurodivergent.

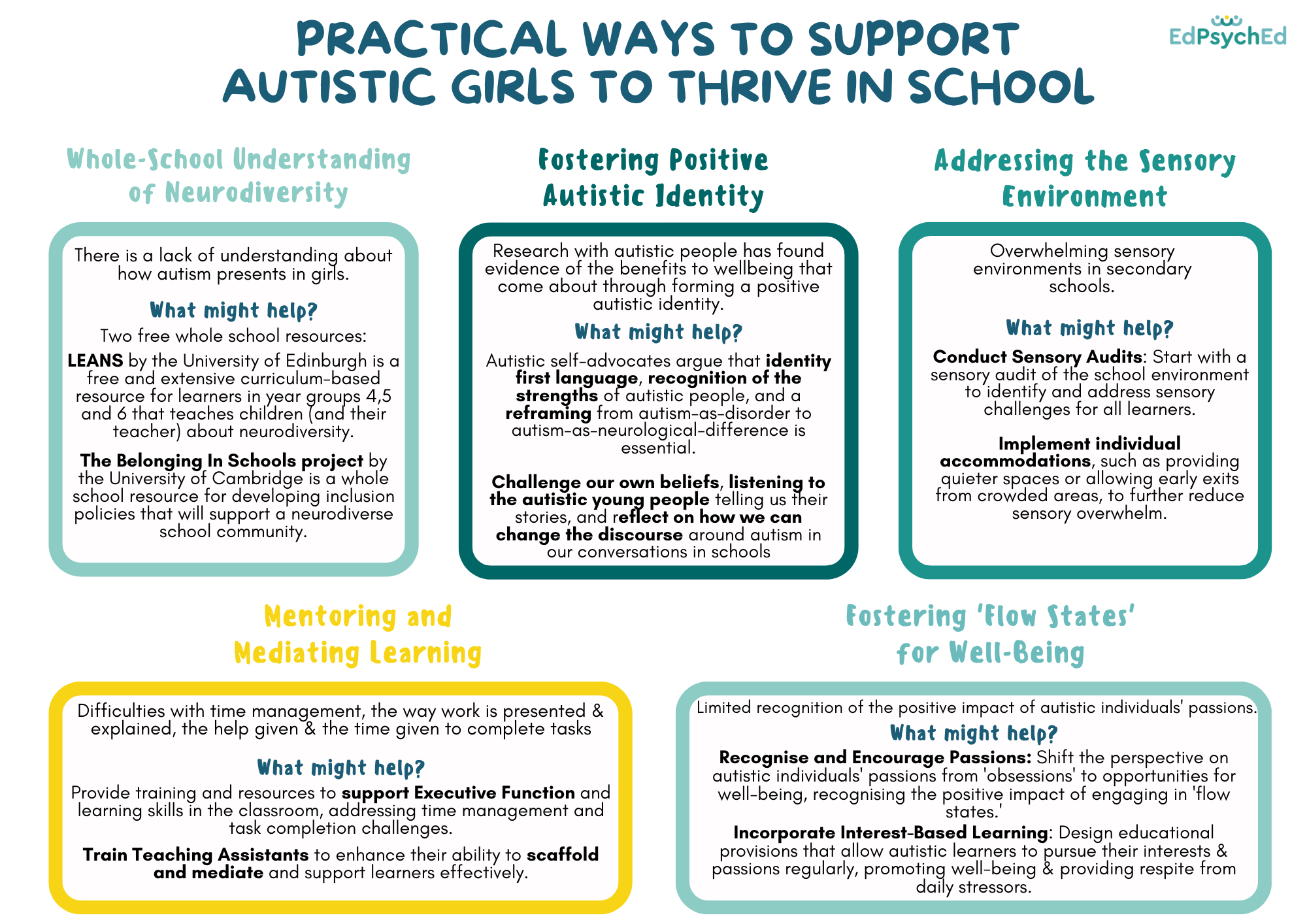

What can schools do to become more inclusive for a neurodiverse school population? Two free whole school resources that have recently been made available are LEANS by the University of Edinburgh, and the Belonging In Schools project by the University of Cambridge. The former is a free and extensive curriculum-based resource for learners in year groups 4,5 and 6 that teaches children (and their teacher) about neurodiversity. The latter, is a whole school resource for developing inclusion policies that will support a neurodiverse school community.

2. Support positive autistic identity:

Research with autistic people has found evidence of the benefits to wellbeing that come about through forming a positive autistic identity. Whilst there is recognition that stigma about autism remains a difficulty, autistic self-advocates argue that identity first language, recognition of the strengths of autistic people, and a reframing from autism-as-disorder to autism-as-neurological-difference is essential.

The language we use matters because identity does not form in a vacuum. The way we come to view ourselves (our self-concept), and as part of groups (our social identity) is a product of our interactions, the feedback we receive from our relationships, and from the messages we pick up in the language used about us and around us.

Addressing the way we think about autism, challenging our own beliefs, listening to the many autistic young people telling us their stories, and reflecting on how we can change the discourse around autism in our conversations in schools is a good place to start.

3. Address the sensory environment:

It is difficult to find a piece of research with autistic girls that does not address the sensory environment of secondary school as a problem. Busy school corridors, school canteens with echoing sounds and strong smells, hectic school transport journeys etc. In any training or advice I give to schools supporting neurodivergent pupils I suggest they start with a sensory audit of the environment.

Again, there may be individual accommodations that are also necessary, such as a quieter place to eat, leaving classes a little early to avoid the crowded corridors and so on, but if we can get things as good as they can be for all learners, we can reduce the sensory overwhelm a little more for neurodivergent learners.

4. Mentor and mediate learning (including the affective aspects):

Many accounts from autistic girls describe difficulties with time management, the way work is presented and explained, the help given and the time given to complete tasks (for example see Please listen to us: Adolescent autistic girls speak about learning and academic success - Pamela Jacobs, Wendi Beamish, Loraine McKay, 2021 (sagepub.com)).

Supporting Executive Function and learning skills in the classroom is a key way to support autistic girls to thrive in school. Not only will this improve educational outcomes, it will also support improved wellbeing through reducing stress. Whilst there are some great strategies we can share, often the best intervention is a relational one.

However, the staff who are most often tasked with supporting learning on a day-to-day basis – Teaching Assistants – have often not been trained in how to mediate learning effectively. In my local authority we have been training Teaching Assistants in MeLSA (Mediated Learning Support Approach). The six-day training covers key psychological theory and provides trainees with evidence-based strategies and interventions to mediate and support learners in the classroom.

5. Curate opportunities for autistic learners to regularly experiences ‘flow states’:

I follow a number of autistic young adults on social media platforms who frequently share about their experiences in vlogs. Initially I went to these online spaces to gain a deeper understanding of autistic experience, but I stayed on those platforms because I loved listening to people talk about, and engage in, the things that energise and fill them with joy.

What I could see in these spaces was people in their ‘flow states’ (see What is 'flow'? (studio3.org) and “In a State of Flow”). Instead of viewing autistic people’s passions as ‘obsessions’ or as something to problematise (how many conversations have you had about learners ‘obsessed’ with technology**?), we might well recognise the well-being that emerges from being in flow states. Enabling autistic learners to pursue their interests and passions in their learning provision will provide well needed respite from the stressors of the school day and promote a good sense of wellbeing.

** A good resource for autistic young people into technology is Spectrum Gaming.

References

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., & Hebron, J. (2020). The school experiences of autistic girls and adolescents: a systematic review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1643154

FOR SCHOOLS:

EBSA Horizons School Staff Training

EBSA Horizons School Training is a comprehensive CPD course for School Staff, which develops understanding and skills (alongside a lot of resources) to support children and young people experiencing difficulties attending school. This course has recently been updated with a new chapter.

Find out more about EBSA Horizons School Training here and register your interest to receive 3 FREE resources from this course.

Family Horizons: Nurturing School Engagement and Wellbeing

Family Horizons offers parents and carers on-demand access to practical strategies, knowledge, and tools across five carefully structured chapters. From understanding attendance challenges to supporting anxiety and promoting family wellbeing, the course brings together professional expertise with real family experiences.

Find out more about Family Horizons here.

FOR PROFESSIONALS:

EBSA Horizons Professionals CPD

EBSA Horizons is a comprehensive CPD course for EPs and other professionals who support schools, which develops understanding and skills (alongside a lot of resources) to support children and young people experiencing difficulties attending school. This course has been recently updated with new chapters.

Find out more about EBSA Horizons here and register your interest to receive 3 FREE resources from this course.

FOR LOCAL AUTHORITIES & MATS:

EBSA Horizons Partnership Framework

A Local Authority wide Emotionally Based School Avoidance (EBSA) initiative to improve attendance and wellbeing in schools.

Providing training and resources for all LA professionals, school staff and parents/carers.

Find out more about the EBSA Horizons Partnership Framework here.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Sign up to receive updates, resources, inspiring blogs and early access to our courses.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.